Welcome to our third and final installment of our “Understanding Clay Bodies” series!

Having previously had a look at earthenware and stoneware, today we’re exploring the development and use of the highly-prized and frequently romanticized clay that is porcelain. With a name originating from the Spanish ‘porcellana’, meaning cowrie shell, this unique clay was once valued as ‘white gold’, and continues to be considered the finest of the main clay types used today.

(Palace Museum in Beijing)

A Brief History of Porcelain

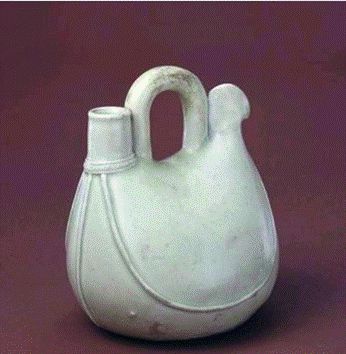

Porcelain was first developed in China somewhere around 2,000 to 1,200 years ago, which is why today wares of this material are often referred to as ‘China’. Some of the earliest evidence of porcelain pieces have been traced to the Eastern Han Dynasty, when China’s famous jade green Celadon glaze was very popular. Its use soon spread throughout Asia and by the time of the Song dynasty, artistry and production reached new heights. The manufacture of porcelain became highly organized at this time, and continued to evolve into the Ming dynasty and beyond.

In the 14th century, the first porcelain made its way to Europe thanks to Marco Polo. Later, after the establishment of Dutch and Portuguese trade routes to the Far East in the 16th century, a market of Chinese porcelain ware created purely for export to Europe emerged.

With the popularity and value of porcelain wares, the race was on in Europe to crack the secret of porcelain and be the first to produce it domestically. German alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger is most commonly credited as being the first European to successfully produce porcelain in 1708 while working for the Meissen factory near Dresden. This has been disputed, however, with some claiming the honor goes to his supervisor, German Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus, and others still saying the first successes were in the UK. Whichever the case, the formula developed at Meissen catapulted the large scale production of porcelain in the continent, with the factory maintaining a world-renowned reputation to this day.

Porcelain Properties

What was it exactly that made porcelain so sought after and so difficult to produce? We mentioned earlier that the name was derived from the Spanish word for cowrie shell, and this is because the surface of the fired clay was as smooth, strong, and beautiful as those shells.

Porcelain is generally composed of three components: kaolin, feldspar and quartz. Kaolin is the key ingredient here, a unique white type of naturally occurring clay which takes its name from Gaoling, the village in Jingdezhen, China where it was first used. It’s composed of alumina silicate, and provides the characteristic white or blue-white color that has become synonymous with porcelain.

In addition to its flawless color, porcelain is renowned for vitrifying at high firing temperatures, which makes it completely non-porous, water tight, and strong. This density also results in a higher shrinkage rate than earthenware and stoneware, with some shrinking as much as 16%.

Porcelain is also famous for its ability to be worked incredibly thinly, to the point of transparency. This is due to its fine particle size, which also allows for finely carved surfaces. This does have its drawbacks however, as it makes it a difficult clay to work with, with a strong memory and a high sensitivity to water.

Types of Porcelain

Porcelain clays can be divided into three main types: hard-paste porcelain, soft-paste porcelain, and bone china. Let’s have a look at the characteristics of each type.

18th century, decorated ca. 1730–40, The MET

Hard-Paste Porcelain

Sometimes called ‘true porcelain,’ this variety was originally made from a compound of the feldspathic rock petuntse and kaolin, and is fired to very high temperatures, typically around 2550°F (1400°C). The earliest porcelains fall into this category. Today, hard-paste porcelain is generally made with a mixture of kaolin, feldspar, and quartz, and is now differentiated from soft-paste porcelain mainly by the firing temperature.

The MET

Soft-Paste Porcelain

This type is sometimes referred to as ‘artificial porcelain’, though it is widely accepted as a genuine type of porcelain. It fires at a lower temperature of around 2200°F (1200°C), which makes it slightly weaker. The lower firing temperature does offer some benefits, however, including a wider palette of colors for decoration and reduced fuel consumption.

Soft-paste is also more granular than hard-paste porcelain, with less glass being formed in the firing process.

Bone China

This clay is composed of bone ash, feldspathic material, and kaolin. It’s the strongest of the porcelains, having very high mechanical and physical strength and chip resistance, and is known for its high levels of whiteness and translucency. Its high strength allows it to be produced in thinner cross-sections than other types of porcelain.

Bone China was developed in the UK, where factories began adding bone ash to their soft-paste porcelains in an attempt to more closely replicate the hard-paste clays of Asia. Because of this, the clay is often referred to as ‘English porcelain’. It remained an exclusively British material for 200 years, before it was finally produced in Japan, then later Russia, China, and the rest of Asia.

Porcelain Glazes and Surfaces

There is a wide range of glazes and glaze processes commonly used on porcelain, from classic clears, to gold lusters, to opaque and vibrant colors. Today, we’re just going to look at a few that are more specifically associated with this elegant clay body.

Dish, unknown maker, 1655 – 65, Jingdezhen, China.

© Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Blue & White

This glaze and stain combo is probably what first comes to mind for most people when they think of porcelain. Its use actually predates porcelain, first appearing in the Tang dynasty (618 – 906), but it was when it found its way onto porcelain that its popularity skyrocketed.

Blue and white is typically achieved by brushing a cobalt stain onto the white clay, and applying a clear glaze on top. It can also be achieved by brushing the cobalt on top of the glaze.

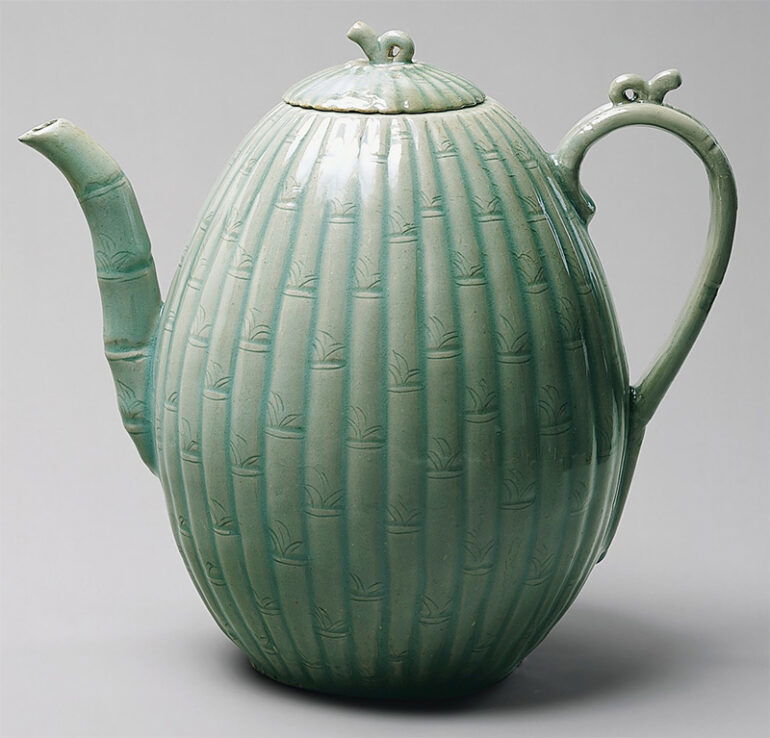

Celadon

Celadons are beautiful transparent green glazes that were developed in China and prized for their jade color. While their popularity was eventually surpassed by the aforementioned blue-and-white porcelain, these glazes are still loved by artists and enthusiasts today.

Celadons are reduction fired, and contain iron oxide to achieve their characteristic color. The celadons that are commonly used today tend to be glossy transparent whereas the ancient versions were more waxy and opaque. They are commonly used over carved surfaces, where the varying depth of the glaze creates a beautiful and subtle color variation.

Indianapolis Museum of Art

Overglaze Painting or Enameling

You may have noticed that a number of the example pieces we’ve included in this blog feature highly decorated surfaces. These are achieved through a process called overglaze painting, which was developed in China and eventually spread throughout Asia and into Europe.

Overglazing can be done on different clay bodies and at different temperatures, but in the case of porcelain, it typically consists of applying a pigment mixed with fluxes onto an already glaze-fired surface, and then refiring the piece at a much lower temperature. The pigments, often called China paints, melt in the kiln and become permanent. This process allows for very fine detail and vibrant colors.

Lustres, such as gold and silver, are a type of overglazing.

Collection of the Ashmolean Museum

As we wrap up our exploration of porcelain, we’re pleased to have this opportunity to celebrate the unique nature of this beautiful clay. From its historical roots to contemporary applications, porcelain’s trademark refinement and mysterious production have shaped its enduring presence in the world of ceramics. This journey has deepened our understanding of the artistry and craftsmanship that porcelain cultivates, and hopefully it has inspired you to give this challenging material a try!

If you would like to learn more about working with porcelain, we have a number of workshop that will be perfect for you! To get you started, consider Ted Secombe’s “Throwing Porcelain,” where this master potter walks you through his throwing process step-by-step. Or if sculpture is more you thing, have a look at Sunkoo Yuh’s “How to make a porcelain sculpture,” where you can follow his process from initial drawings to an intuitive approach to working with porcelain.

Responses