Welcome to Part Two of our “Understanding Clay Bodies” series, where we’re doing a deep dive into the unique features of the three main types of clay: earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain.

Having unraveled the uniqueness and historical significance of earthenware in our initial installment, we now turn our attention to another venerable member of the clay family: Stoneware. With its rich history, distinctive qualities, and versatile uses, stoneware clays stand as a testament to the evolution of ceramic artistry through the ages.

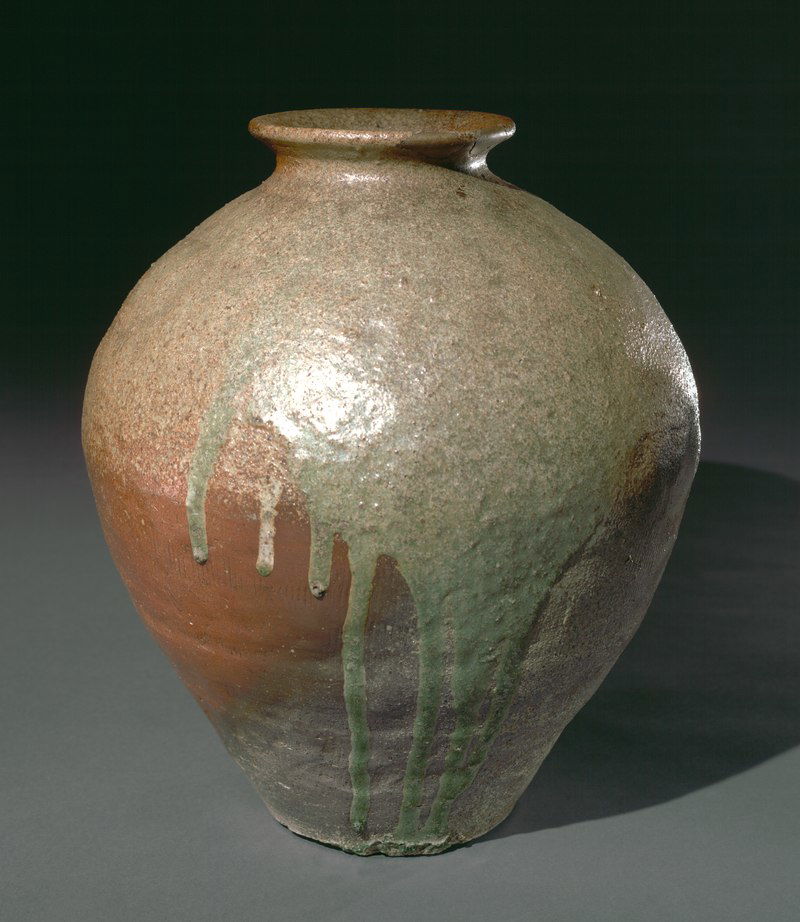

with partial ash glaze

A Brief History of Stoneware

Stoneware has become a mainstay clay type for many contemporary makers, so it’s easy to think of it as ordinary. In the history of ceramics, however, stoneware is actually a relatively modern invention, and its development marks a significant technological advancement.

Unglazed stoneware was first made in China around 2000 years ago, and is thought to have developed naturally as an extension of higher temperatures achieved from early development of reduction firing. It quickly became commonplace in medieval China and Japan, though in China its use was reduced by the time of the Ming Dynasty, due to porcelain’s development and resulting surge in popularity. Stoneware was also in use in Korea by the 5th century, and was of a quality nearing that of porcelain.

Stoneware was much slower to be developed in Europe, and was discovered independently of Asia. This delay was caused by the use of less efficient kilns, as well as less access to deposits of suitable clays. Its first use was in Germany in the 13th century, where it was produced in regions along the Rhine, and quickly became a highly prized export to the rest of Europe. While stoneware was not manufactured in Britain until the early 17th century, the country eventually became the most inventive and important European maker of fancy stoneware in the 18th and 19th centuries.

What was it about stoneware that made it so desirable and important? Let’s have a look at its unique characteristics below to find out.

Stoneware Properties

Stoneware is a secondary clay, meaning that when it’s formed in the environment, it picks up impurities which require it to be processed for use. It’s primarily composed of quartz, clay, and feldspar. This composition allows stoneware to undergo the process of vitrification (glass formation) when fired to maturity, though typically it only undergoes partial vitrification and maintains a low degree of porosity. While stoneware clays do occur naturally, they are less common than earthenwares, and additions are commonly required to achieve the high-firing results.

The partial vitrification of the clay results in a clay that is much less porous than earthenware. This allows for a significant advantage, which is that the clay does not need to be glazed in order to be water-tight. It also makes the fired work more durable for outdoor use in climates that experience freezing.

Stoneware clays are noted for their excellent working properties, which is due to their being ball-clay-based. Ball clays are much more forgiving than kaolins (which are the basis of porcelain clays), featuring high plasticity, fine grain quality, and high greenware strength.

Stoneware can be once-fired or twice-fired. While generally classified as a medium to high-firing clay, firing temperatures can vary significantly, typically from 2012F/1100C to 2372F/1300C depending on the flux content. It’s even possible to create a stoneware body that vitrifies at Cone 02! The clay body can be fired in oxidation or reduction, with each process creating unique aesthetic qualities.

Stoneware ranges in color, from off-white, to deep brown, to speckled. It is often used with additions, such as paper, grog, or body stains.

Types of Stoneware

Just as with earthenware, stoneware comes in a variety of types based on differing regions and uses. Typically, ceramic artists work with stonewares that are classified as traditional (inexpensive bodies of any color that are made of fine-grained secondary, plastic clays) or fine stonewares (made from more carefully selected, prepared, and blended raw materials). Within these two categories lie a number of unique clays that have become known for their characteristic qualities. We’ll look at a few of these now.

Yixing Clay

This stoneware originates in Jiangsu Province, China, and has been used in Chinese pottery since the Song dynasty (960–1279). Yixing clay is a mixture of kaolin, quartz and mica, with a high content of iron oxide. It comes in purple, red, and beige, and is most commonly used in the famous Yixing teapots. These teapots are easily recognized for their smooth, rich, unglazed surfaces that are made possible by the qualities of this clay.

restaurant ware made of ironstone china

Ironstone

Ironstone clay was developed in Staffordshire UK in the 19th century, eventually making its way to the US by 1850. It shares some properties with earthenware and is sometimes classified as such, but its vitrification makes it much closer to stoneware. While often cited as containing the mineral ironstone, the clay doesn’t actually contain this ingredient. Rather, the name stems from the clay’s superior strength which allowed for the production of ornamental objects of considerable size.

Ovenware

Ovenware refers to clay that is formulated to withstand the thermal shock of being placed in an oven, and is typically used for making things such as casserole dishes. It is different from flameware, which is designed to handle direct flame. Ovenware clay is typically made from a high-firing stoneware that is low in ball clay, and which contains pyrophyllite, fire clays, and lithium feldspars, such as spodumene or petalite. These ingredients help to lower the thermal expansion of the clay, making it crack resistant when used in the oven.

Raku Clay

The intensity of the firing process used for North American style raku requires a robust clay with high thermal shock resistance. And while the low firing temperature used for raku may lead you to think that earthenware is your best bet, it’s not the ideal choice if you are after strong blacks on your unglazed surfaces. The iron content of these clays resists the carbon trapping so often sought after in raku, as does their low maturation point. Instead, the ideal clay for raku is a stoneware clay that features the addition of Kyanite. This ingredient increases the thermal resistance of the clay, while the higher vitrification point of the stoneware allows for strong blackening of the clay (as its porous unmatured surface allows smoke to be drawn in more easily). Raku clays are widely available from most clay manufacturers, and the recipes can vary. Heavily grogged varieties are common, but finer bodies are also available.

Common Stoneware Glazes

With the development of stoneware clays and high fire kilns, a whole new world of glazes opened up to ceramic artists. Stoneware glazes are known for their earthy tones, though the development of inclusion stains has allowed for vibrant colors at these high temperatures as well. The common use of reduction firing with stoneware also led to interesting and atmospheric glaze effects that were previously unseen with earthenware clays. Broadly speaking, stoneware glazes can be divided into three main categories, which we’ll discuss below.

Feldspathic Glazes

These glazes are typically made of feldspar, silica, calcium, and clay, with metal oxides added to give the glaze color. As you can guess by the name, feldspar is the key ingredient here, lending its high fluxing properties to create fluid glazes. A number of iconic glazes fall into the feldspar category, including those below.

(1894-1985)

Shinos

Shino glazes originated in Japan, and are used on stoneware clays in reduction firings. A glaze type full of personality and mystique, shinos produce colors from cream, to rich oranges and browns, with flashes of red or metallic possible. They are prone to crawling, crazing, pinholing, and carbon trapping, which, while considered a fault in most other glazes, are embraced as part of the character of the glaze.

Originally Shinos were a two-part mix of about 70-80% high-alumina, high-sodium feldspar and 20-30% clay, though today’s recipes are often adjusted to achieve glossier and more food-safe surfaces.

Tenmoku

This is an iron-rich reduction glaze originating in medieval China, though its name comes to us from Japan, where it was later popularized. While it can be used on both stoneware and porcelain, the iron present in many stoneware bodies is known to give it extra depth. This is a glaze that can vary widely based on the clay, firing schedule, and cooling process. It is perhaps best known for its effect of breaking red over edges, with an otherwise glossy and near-black appearance. It can also result in a maroon glaze with gold or black flecks. It is a very fluid glaze that gives a strong sense of movement.

Ash Glazes

Ash glazes are those made with the ashes of wood or other plants, with their first use during the Shang period in China around 1500 BCE. It’s believed that these glazes initially developed by accident as ash from the burnt wood in the kiln landed on pots. Ash glazes are earthy in color, ranging from brown, to green, or yellow, and are easily identified by their characteristic dripping effect.

Studio Pottery Bottle Vase

Salt Glaze

One of the only significant ceramic innovations of medieval Europe, salt glaze was first developed in Germany in the early 1400s. While no longer used at an industrial level due to its high creation of air pollution, salt glazes are still used by studio potters around the world. The glaze is best known for its orange peel texture, and ranges in color from clear to brown, with oxides such as cobalt commonly used to add decorative effects. The glaze is created in-kiln by adding common salt towards the end of the firing. Stoneware clays high in silica work best, and reduction firing helps to increase the fluxing of any iron particles.

Soda Glaze

Soda glazes developed as a response to increased awareness around the environmental impacts of salt firing. The process was developed in 1970s at Alfred university by a couple of graduate students by combining baking soda and soda ash. This combination produces carbon dioxide as a byproduct, rather than hydrochloric acid, making it much safer for both the environment and us.

Like salt firing, soda firing is a vapor firing process, where the material is added to a kiln of unglazed pots during the firing process. The movement of the material and resulting vapor throughout the kiln creates distinctive flashing patterns across the pots. The colors produced are more vivid than those of salt firing, ranging from clear, to grays, yellows, oranges, red, and browns. The addition of coloured oxides can bring in blues and greens. Like salt glaze, soda can also produce an orange peel effect.

In concluding our exploration of stoneware clay, the second installment in our blog series, we’ve uncovered the resilient and versatile nature of this clay type. From its historical roots to contemporary applications, stoneware’s distinct textures and intricate firing techniques have shaped its enduring presence in the world of ceramics. This journey has deepened our understanding of the artistry and craftsmanship that stoneware inspires, setting the stage for the final part of our series where we’ll unravel the mysteries of porcelain clay!

If you would like to learn more about stoneware glazes, as well as those for other firing ranges, check out Matthew Blakely’s workshop Making Glazes from Rocks, Clays, and Ash. In this unique course you’ll learn how to collect, process, and test found materials to make your own unique glazes!

And if you missed out on the first installment of this series, be sure to check it out here!

Responses