As you’ve begun your exploration of ceramics, you’ve likely discovered that clay is primarily divided into three different categories: earthenware, stoneware, and porcelain. But what exactly separates these clays, and how do you know when and how to use each one?

In this new blog series, we’re embarking on a journey to unravel the unique qualities and characteristics of each, as well as looking at their history and common uses. In our first part of the series, we’re taking a close look at earthenware.

Middle Joon Vessel

A Brief History

Earthenware, with its rustic allure and historical significance, has been a cornerstone of human craftsmanship for millennia. From humble beginnings in ancient civilizations to its presence in contemporary pottery studios, earthenware clay has left an indelible mark on the art and science of ceramics.

Earthenware was the very first type of clay molded by human hands, with pit-fired earthenware dating back as early as 29,000–25,000 BCE. It remained the sole clay in use until stoneware was developed in Asia around 2600–1900 BCE, and continued to be the only type used in Europe until the Middle Ages. It is the clay that gives the characteristic orange tinge to Ancient Greek pottery, the clay that was used to construct the famous Terracotta Warriors of 200 BCE, and the clay which formed the foundation for the decorative maiolica tiles of 15th century Spain, Portugal, and Italy.

Today, earthenware is still broadly used, with its popularity varying by region. In North America, the trend over the last century has been towards stonewares and porcelains, but with the recent rise in environmentally conscious practices, earthenware is seeing a resurgence. As you’ll see here, it is a versatile clay that can be used for any making method, and which offers unique physical and aesthetic qualities.

Main Characteristics

Earthenware clays, as you may have surmised from their ancient usage, are clays that exist naturally. They can be used ‘as-dug’, meaning that additions of other materials are not necessary for the clay to be workable and fireable, unlike porcelain. Today, we commonly use prepared earthenware clay bodies, particularly those of us who are not lucky enough to have clay deposits nearby. In much of the world, earthenware continues to be dug locally, with minimal processing used.

Earthenware clays come in a variety of colors when unfired, including red, gray, brown, yellow, and even green. Once fired, most clays transform to shades of red, off-white, or buff. A number of additions can be added to earthenware clays for varying effect, such as the addition of powdered mica to increase thermal shock resistance, or grog for increased strength while sculpting.

Non-Vitreous

What is most notable with earthenware clays is that they are non-vitreous clay bodies, meaning that they do not form glass particles when fired. Instead, earthenware goes through a process called sintering. Unlike vitrification, where the formation of glass helps to bond and harden the clay particles together, sintering involves adjacent particles bonding or fusing together at points of contact by the migration of molecular species across the boundaries. Because earthenware sinters rather than vitrifies, it exhibits a number of unique characteristics.

One of its primary characteristics is that earthenware remains porous even when fired to maturity. This provides the clay with some benefits as well as drawbacks. One benefit is that porosity allows for greater thermal shock resistance (surviving direct flame twice as long as most stonewares and porcelains!). This is because the tension and compression created by thermal expansion is more easily dissipated by earthenware’s less densely packed particles.

The porosity of earthenware also means that the clay is breathable, making it perfect for certain applications, such as plant pots, building materials such as bricks, and even electricity-free refrigerators! On the flip side of this, the breathability means that this clay does not hold liquids well, and the gaps between the particles can offer space for bacteria to grow if the pot is not thoroughly cleaned or is left wet. It’s for this very reason that burnishing and terra sigillata were developed (at least in part), as they reduce the surface porosity by compression or by filling the gaps with finer particles. And, of course, the addition of a properly fired glaze will make a vessel water-tight.

Another drawback of this feature of earthenware is that its absorbent nature makes it unsuitable for outdoor use in regions that experience frost or freezing. Water, of course, expands as it freezes. If water has been absorbed into the walls of a pot, this expansion will cause cracking or breakage.

Low-Firing

Earthenware clays are also noted for their relatively low firing range, maturing between cones 010-04 (1652F/900C – 1940F/1060C). While this, combined with the non-vitrifying nature of the clay, has led many people to assume that earthenware is weaker than stoneware of porcelain, there is research to suggest that it is actually the strongest of the three, providing it is properly fired!

One of the benefits of this low maturation point is the broad range of glaze colors that a low firing range permits. Many natural color-producing oxides lose their potency at higher temperatures, becoming muted and dull, or even disappearing altogether. This is particularly true for those used to produce yellows, reds, and pinks. Since earthenware cannot be high fired, this color loss is not an issue, and a broad range of incredibly vibrant hues can be created. While manufactured stains have increased the firing range for many colors, they remain more expensive to produce and use.

The low firing range makes this clay ideal for pit-firing and other alternative low firing processes, and of course this is how the earliest pots would have been fired. This makes the firing process much more accessible as electricity or gas are not required. It also permits the unique aesthetic qualities of smoke firing, which do not occur as intensely at higher temperatures or with denser clays.

For the modern potter, one of the biggest benefits of earthenware’s low firing range is its reduced environmental impact and energy cost. With a maximum temperature almost 300F (148C) lower than a typical mid-range stoneware, the energy savings is significant. This is of particular benefit for artists with high production rates.

Types of Earthenware

Earthenware clays vary greatly based on the local mineral content, and these variations can attribute unique features to the clay. As a result, a number of different earthenware bodies have been popularized throughout history and continue to be available today. Let’s look at a few below.

Terracotta

This is probably the most commonly used earthenware body. In fact, it is so common that the name is often used interchangeably with the term earthenware, though it does exhibit features that are not common to all bodies in this category. Terracotta is noted for its characteristic orange color which is caused by rich iron deposits in the clay, as well as its versatility. It is well suited to wheel throwing, hand-building, sculpting, and architectural applications. Terracotta can also refer to any red earthenware that has been left unglazed, such as with classic plant pots or roof tiles.

ctx=86d7c06e5425dfd31ea9178b369ede5674edebbc&idx=2

Creamware

Creamware is a fine white earthenware that was first produced in England in 1750. Made from white clays from Dorset and Devonshire combined with an amount of calcined flint, creamware is traditionally glazed with a clear lead glaze. It was most famously used by Josiah Wedgewood, who improved upon the original recipe by incorporating china clay. This created a lighter-colored and stronger clay body. With this development, creamware’s use quickly spread throughout Europe and into the USA.

collecting-antique-yellowware-pottery/

Yellowware

Another body that was developed in the UK and later found its way to the United States, yellowware gets its name from its distinctive yellow color. Production of yellowware started in Scotland in the 17th century, and it continues to be used today. It is typically glazed with a clear alkaline glaze that shows off its unique color.

Common Earthenware Surface Treatments

Throughout the centuries, a broad number of surface treatments have been used on earthenware clays, and many of these remain unique to this clay type. Most of these processes remain in use today, and we’ve outlined a few of them below.

Engobes & Slips

Both engobes and slips have long been used on earthenware pots as a form of decoration. The earliest evidence of engobe use traces back to 3000 BCE! While slips typically consist of a mixture of clay, water, and colorants which must be applied to the work prior to firing, engobes contain the addition of a flux. This allows the decorative paste to be applied not just to leather-hard work, but bisque-fired pieces as well, making it much more versatile.

In addition to being used as decoration, both engobes and slips have been used on earthenware to make pieces more water tight, and to also add a base color layer between the clay and the glaze.

Terra Sigillata

Terra sigillata is a super-fine slip that can be buffed to produce a fine sheen. It is composed of very fine clay particles that help to improve water-tightness by filling the gaps between the clay body particles, and it forms a smooth skin on the surface of the work. While it can be used on a variety of clay types, it is most commonly used on earthenware as the characteristic shine is lost at higher firing temperatures. It can be used to create a satin-like unglazed surface, and also enhances the effects of alternative low-fire processes such as smoke firing and aluminum foil saggar firing.

Lead-Glazed

The first evidence of lead glazes dates to the first century BCE during the Late Hellenistic period in Anatolia. Lead lowers the melting point of glazes, making it an ideal ingredient for earthenware glazes. It has been used both as a clear glaze and with the addition of colorants. These glazes continue to be used by artists around the world today, and despite many peoples’ misgivings about the use of lead glazes on functional pottery, they can food safe provided they have been properly fired.

Franco Xanto Avelli (Italian, 1487-1542)

Tin-Glazed

This glaze originated in 8th century Iraq, spreading throughout the Middle East, and eventually finding its way to Europe via Spain. Its use was widespread in the Mediterranean, and was instrumental in the development of maiolica and faience techniques. Tin glazes are opaque, glossy, and white glazes, and are essentially lead glazes with the addition of tin oxide. The neutral white background of the tin glaze is typically decorated with colorful oxides, either through direct brushing on the unfired glaze, or as an overglaze requiring a third firing.

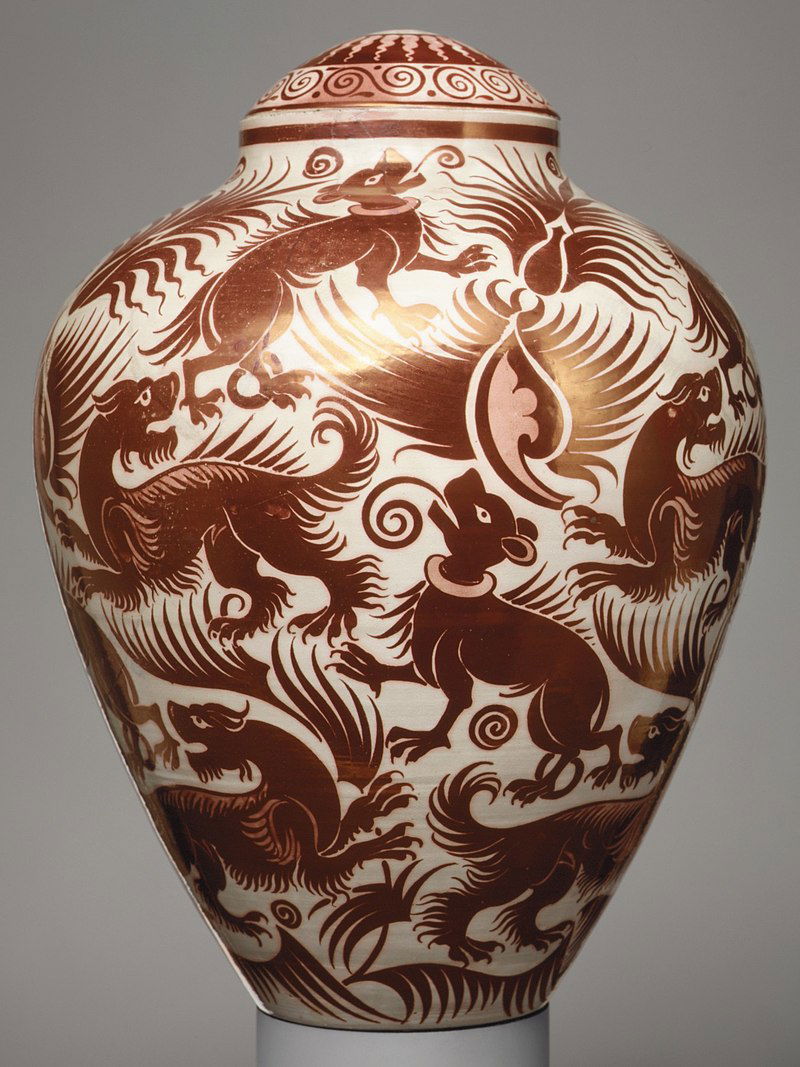

Luster

Another glaze process that has its origins in Mesopotamian Iraq, luster is an overglaze that creates a metallic or opalescent shine. Original recipes were composed of metal salts of copper or silver, mixed with vinegar, ochre, and clay. It is low fired with reduction to create the characteristic sheen. Lusterware was very commonly used throughout the Islamic world, and also experienced a period of high popularity in 18th and 19th century Britain, where the use of platinum in luster glazes was introduced. Lusters are still used by artists today as a design highlight or for high-impact surfaces.

With ancient roots and modern applications, earthenware is a clay rich in history, aesthetic traditions, and versatile uses. We hope today’s article has not only shed light on the unique qualities and characteristics of earthenware, but has also set the stage for a comprehensive understanding of the diverse realm of ceramic clay bodies.

In the upcoming segments of this blog series, we’ll be diving into the history and uses of stoneware and porcelain, providing you with even more inspiration for your ceramic practice!

If you are keen to develop your earthenware surface decoration techniques, why not sign up for Elina Esther Jurado’s workshop Intro to Terra Sigillata? Or if burnished surfaces have captivated your imagination, why not check out Om Prakash Galav’s workshop How to make a fine Terracotta Burnished Pot. Both programs will walk you through these earthenware processes step-by-step, easily allowing you to expand your low-fire clay skills!

Responses